The awful truth about college book sales

Kaelan Unrau CONTRIBUTOR

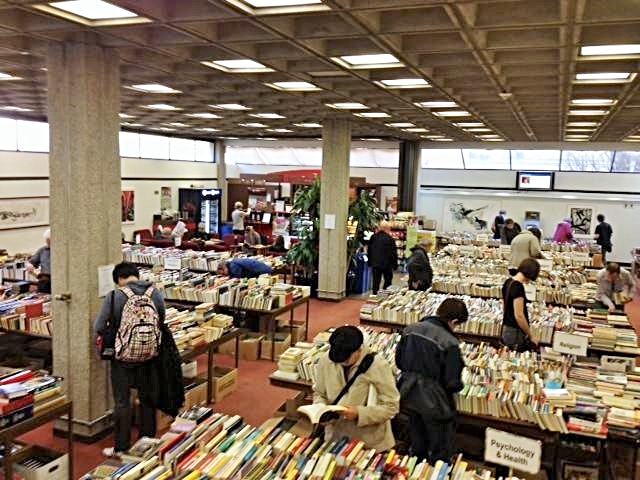

Photo: A scene from the 2012 St. Mike’s Book Sale in Kelly Cafe (USMC).

Oh Autumn! Season of mists, mellow fruitfulness, and varsity book sales. At the University of Toronto, four colleges — Victoria, St. Michael’s, University and Trinity — host annual book sales of their own, through which tens of thousands of pre-loved titles are paired with eager new owners.

That is how it should be. But this year, something felt off. The books — they looked older, shabbier. Where once one might have found a mint copy of Heaney’s Beowulf, there now stood The Selected Works of Carlyle: Volume 3 in rag-tag hardcover. (What had become of the first two volumes I do not know.)

Perhaps it was just a bad haul? Surely, the used-book supply, like any other yearly yield, must see its ups and downs. But I suspect the operation of a far less innocuous cause.

Let me explain how these suspicions germinated. On the opening day of the Victoria College sale, as I was skimming across the tables of general fiction, I came upon a Reader’s Digest edition of Silas Marner. It was a handsome book — a hardback with tasteful illustrations — although slightly marred by an inked inscription on its title page. I opted for a different copy. A few days later, I was browsing the shelves of a Bloor Street used bookstore when what did I spy but another Reader’s Digest Silas. I flipped to the title page. There was the very same inscription, staring back out at me.

Thus, I hereby contend that book resellers — yes, book resellers — are ruining our beloved book sales. Book resellers, who, armed with a cardboard box or four, indiscriminately snag any title with presumptive resale value. Eliot. Dostoevsky. Penguin Classics. Any newish looking softcover in good condition. As a result, an essential dimension to these sort of sales — the thrill of the hunt, the community of fellow bibliophiles — has been compromised.

Yet resellers also pose a problem on a strictly economic level. If people are purchasing books at book sales and proceeding to flip them at used bookstores, then these sales are in effect subsidizing the efforts of the third-party resellers. If one wishes to support the Kelly Library, say, then one should elect for a direct monetary donation. Its value would go further. Conversely, the library, if it truly wishes to maximize its fundraising revenue, should cut out the middleman and itself sell to used bookstores directly. And as for those who wish to donate used books, the directive is similar: sell the books yourself and donate the profits.

These solutions provide little solace if one actually likes book sales. But what are the alternatives? At present, I can think of at least two avenues for book sale reform. First, organizers could implement transaction caps. For instance, attendees could be barred from purchasing more than twenty books at a time. People could always buy more than twenty books, but it would take more time to do so, which would have the effect of decreasing the profit margins for reselling.

Second, organizers could ensure that attractive stock gets added to the sale tables throughout the day. So long as the “best time” to hit up a book sale remains uncertain, resellers face greater risk and thus enjoy reduced economic incentives. At the same time, non-resellers would have a greater incentive to visit a book sale after those critical first few hours.

Of course, spurning resellers means spurning part of the present-day book sale client base. But these sales are more than just economics, right?